Matcha: 7 Myths and Misconceptions

In the past few years, matcha has had a massive surge in popularity in the West. While this has made it easier to buy matcha outside Japan, it has also led to the proliferation of many myths and misconceptions surrounding this Japanese tea. Here, we'll take a look at seven of the most popular myths and misconceptions and see if there is any truth to them.

Myth 1: “Ceremonial Grade” Matcha exists

Verdict: False

While you’ll see many matchas marketed as ‘ceremonial grade’ as opposed to ‘culinary grade’ or ‘latte grade’, the truth is that these grades don’t exist, at least not in any meaningful way. As there are no rules or organisations that regulate these terms, brands and companies are free to label whatever they want as ‘ceremonial’, regardless of its quality. Every company has its own definition of what qualifies as ‘ceremonial grade’, which can make shopping for matcha very confusing and misleading, especially when little or no other information about the tea is given.

While at a glance, these terms can be useful to get a rough idea of whether a matcha is drinkable on its own or needs to be tempered with sugar and milk, it ends up creating a false dichotomy of ‘ceremonial’ and ‘culinary/latte’ grades, ignoring the wide variety of qualities and styles that matcha has to offer, especially within the ‘ceremonial’ range.

For example, among tea ceremony practitioners, matcha is generally thought of in three rough tiers of increasing quality: keiko, usucha, and koicha. Keiko grade is used for practice and lessons, usucha is used for serving thin tea to guests, and koicha for serving thick tea. Confusingly, all three of these very different teas would likely fall under the umbrella of ‘ceremonial grade’ outside of Japan.

While the traditional usucha/koicha system is still used by centuries-old tea producers who blend matcha to fit into these categories, more modern styles of matcha production, such as unblended single-origin teas, often don't operate under the same system.

In a future blog post, we will explore the many factors that determine matcha quality including cultivation, shading, picking, processing, and grinding. This will help you be more informed when deciding which matcha to buy.

Myth 2: Greener is higher quality

Verdict: Mostly true

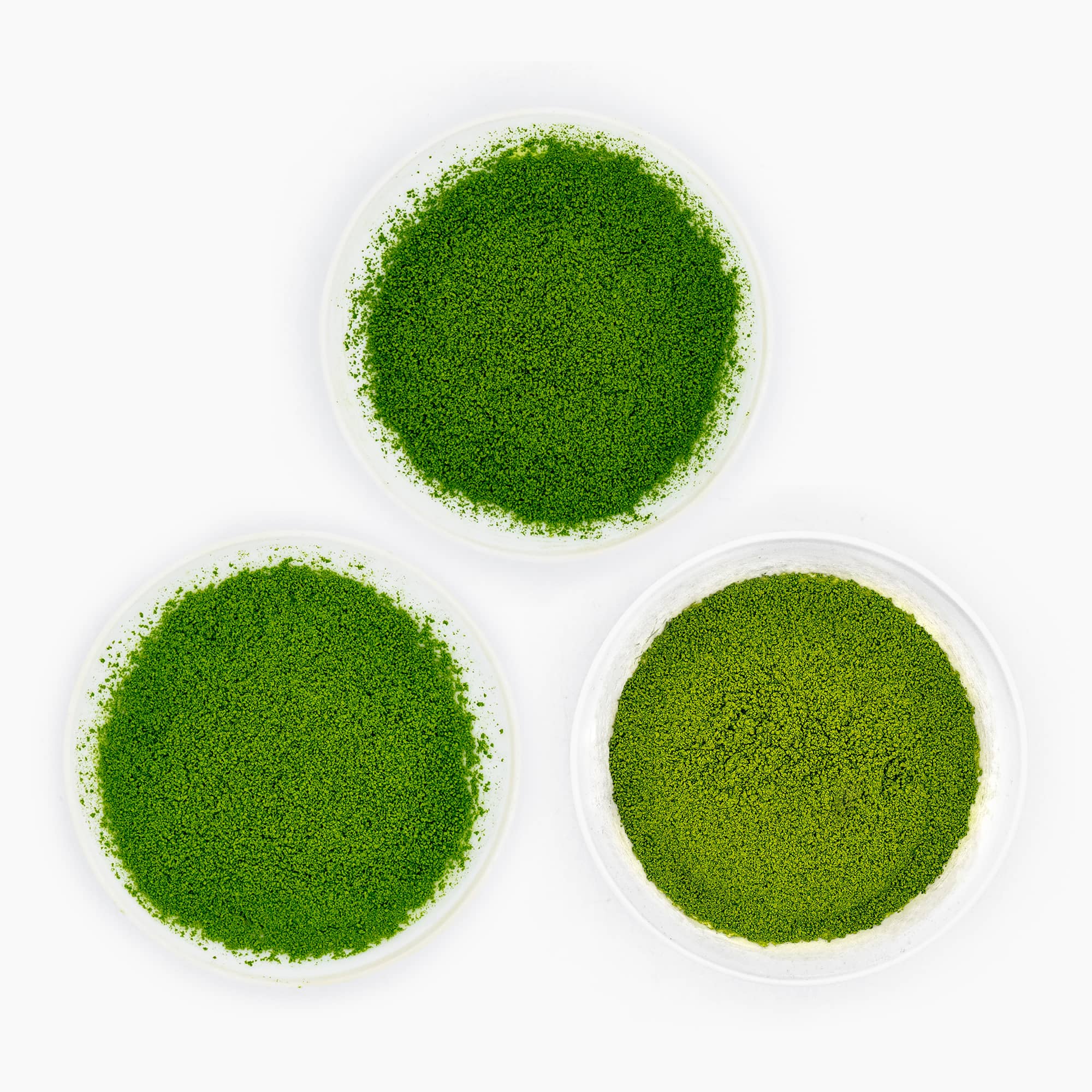

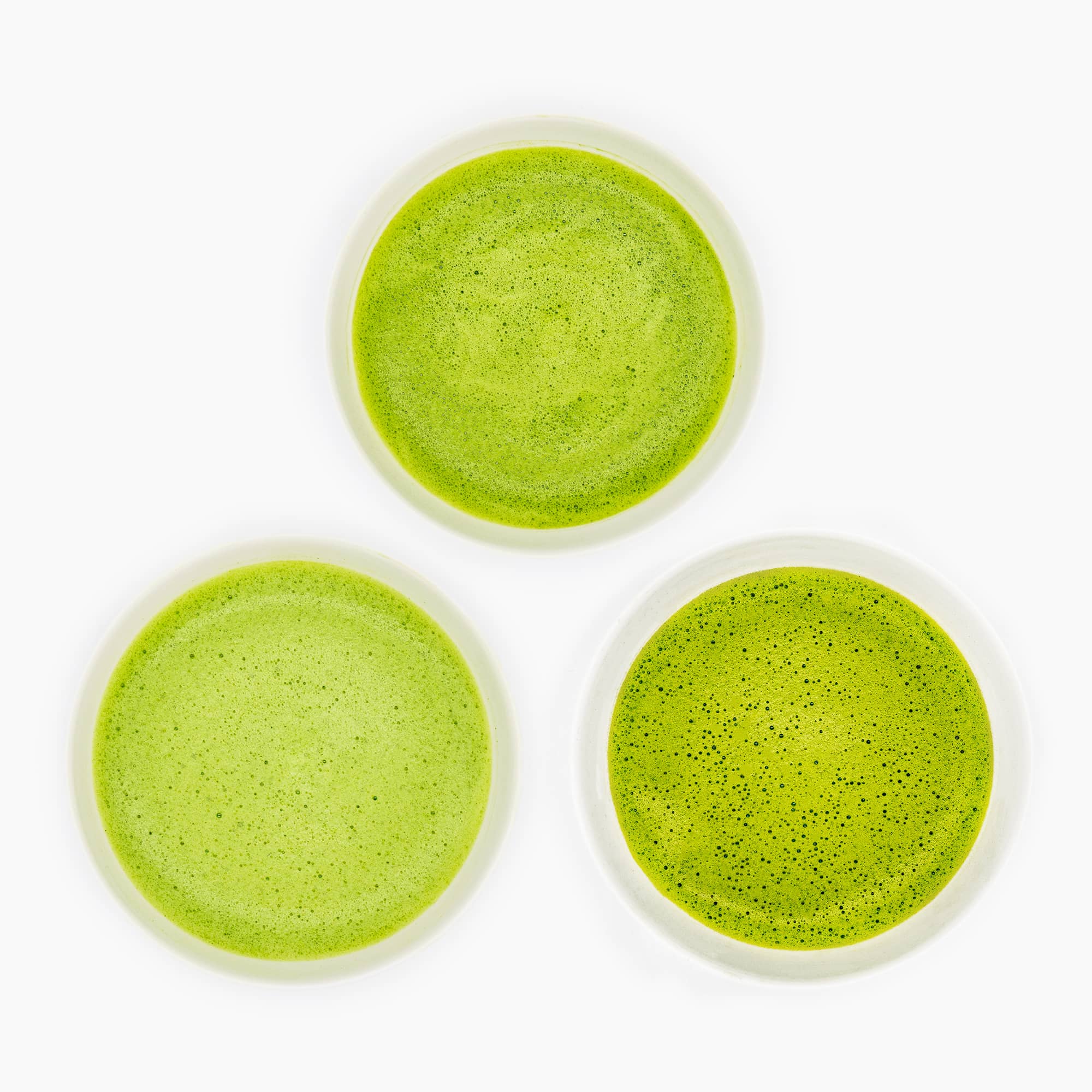

You’ll often see matcha colours compared through a smear test, where a sample of matcha is smeared on white paper. This test is a useful way to examine two aspects of a tea: its colour and texture.

Generally speaking, higher quality matchas are a vibrant, more saturated green and have a smooth texture with a small and regular particle size.

However, this is not always true. For example, straw-shaded teas, which are generally considered the highest quality, are often not as dark as leaves grown under artificial shading. To learn more about shading types, check out this post.

Outside of quality, there are other factors that can affect the final colour of matcha, such as the cultivars used or strength of the hiire (火入) or final firing of the tea. While these factors greatly affect flavour, they are not necessarily linked to quality.

In the picture above, the teas are arranged in order of increasing quality, from left to right. However, the middle matcha has a richer green, despite being of lower quality compared to the matcha on the right. This is due to a combination of shading style and cultivar.

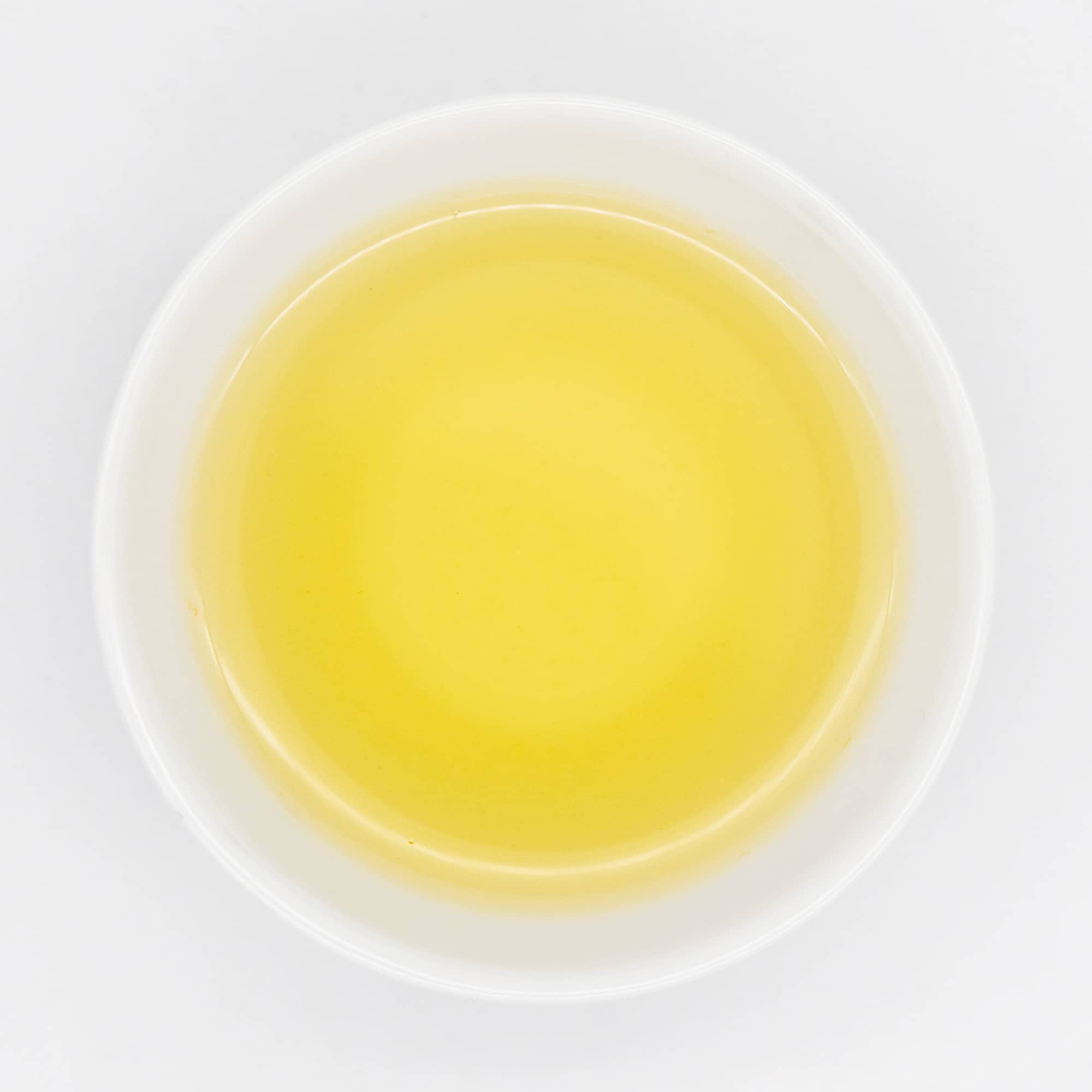

Lastly, colour can be affected by the tea’s freshness. If properly stored, tencha (the raw material to make matcha) can be kept fresh for years, but once ground into matcha, the tea will begin to oxidise and deteriorate with exposure to air, light, and humidity. This can cause once vibrantly green matchas to become dull and yellow-brown.

Myth 3: Organic matcha is better

Verdict: It’s complicated

The details and complexities of organic tea farming deserves its own blog post, but here are some of the main points.

There is no doubt that organic farming is more environmentally sustainable and responsible, however it is not without its challenges.

Certification

Becoming JAS certified organic is a long, difficult, and expensive process for a farm or producer to undertake, and due to the nature of agricultural runoff, it is a process that neighbouring farms must go through together. As such, it is easier for larger scale producers to obtain certification than it is for smaller farms.

There are many of these smaller farms in Japan that are producing high-quality tea in a more natural, organic, or near-organic way. They may still be pesticide-free and use little to no chemical fertiliser, but due to the difficulty of JAS certification, are not yet certified as organic. Many of the teas that we offer fall into this category.

The cost of certification and the costs of organic cultivation (such as decreased yield) are also passed on to the consumer, with organic teas generally being more expensive than conventional teas of similar quality.

Taste

Generally speaking, organic teas taste different than those grown conventionally, often in an undesirable way. The powerful, umami-rich, vibrant taste that is expected from modern Japanese tea, especially matcha, is highly dependent on heavy fertilisation. While large scale operations will mostly use chemical fertilisers, many high-end matcha producers will use a mix of chemical and natural fertilisers (such as other tea plants, grass, fish, squid, pressed canola seeds, etc), or exclusively natural fertilisers. However, these natural fertilisers are not necessarily certified as organic, meaning the tea cannot be certified either. In short, it is harder, but not impossible, to produce organic matchas that compete with conventional teas on taste.

Taste, of course, is a matter of preference. More naturally grown matchas, including certified organic matchas, tend to have less umami and fewer of the ‘marine’ notes that some Japanese green teas have.

Myth 4: Matcha is always bitter

Verdict: False

As a result of matcha’s inherently high caffeine and catechin levels, most low-quality matcha will have a predominant bitterness. However, higher quality teas that have been carefully grown, well-shaded, and skillfully picked and processed can have little to no perceived bitterness due to their high levels of amino acids. You can read our dedicated blog posts to learn more about the science of bitterness and flavour in tea and how shading affects taste.

Myth 5: Matcha is simply green tea powder

Verdict: False

While it is technically true that matcha is technically a type of green tea powder, not all green tea powders are matcha — it’s like squares and rectangles.

Unlike simple powdered sencha called funmatsu-sencha in Japanese, matcha is made from ground tencha, which is grown, picked, and processed differently. You can read more about how tencha is made here.

To be made into matcha, the tencha must then be ground slowly in a specially cut granite mill called a chausu or ishiusu (茶臼・石臼). The 23kg (~50lbs.) weight of the upper millstone crushes the tencha into a superfine powder, with particles measuring around 5-10 microns. Modern commercial matcha mills are 33cm in diameter and can only produce 40g of matcha per hour. If they spin any faster, they will generate too much heat, which ruins the tea. If they were made any larger, they would grind the tea too fine.

Myth 6: You need fancy equipment to make matcha

Verdict: False

Matcha is a very old type of tea (with the earliest proto-matcha invented in China around 1000 years ago), meaning it is quite simple to make and drink: all you really need is a bowl, a whisk, and a sifter. In place of a bamboo whisk, you can certainly try a milk frother, blender, or simply shaking in a bottle, however, we definitely recommend learning how to use a chasen as it is perfect for the job. Here’s our guide on making tea for absolute beginners.

Myth 7: Matcha has to be foamy

Verdict: False

Though the ability to produce a fine foam can be indicative of a matcha’s quality, you don’t necessarily need to have foam to have a good bowl of matcha.

The foamy bowl of matcha you’ll typically see on instagram is called usucha (薄茶 - thin tea). This isn’t the only traditional way to make matcha, however. Koicha (濃茶 - thick tea) is made four times as strong and and is kneaded into a thick syrup, without any foam whatsoever.

Even with usucha, there are many schools of tea ceremony that prefer little to no foam on their tea. So whether you like foam or not, the choice is up to you. To read more about how foam can affect the taste of matcha, check out our little experiment here.

These were just seven common matcha misconceptions. If you have any more questions about matcha, you can learn more about it here, and you can explore our selection of matcha to find your favourite style.